‘See how she leans her cheek upon her hand.

O that I were a glove upon that hand, that I might touch that cheek!’

William Shakespeare (Romeo and Juliet)

O that I were a glove upon that hand, that I might touch that cheek!’

William Shakespeare (Romeo and Juliet)

What can inspire, dazzle, excite, bring joy, enliven all the senses? Could it be the poetic prose of the romantic poet: the colourful brush strokes reflecting an artist’s impressions: the lingering chords playing with the heart strings strummed by a maestro, or the crafted language given to us by a wordsmith? Visionaries and artisans sharing their unique imprint on the canvas of life that offer a sensory feast to our souls.

But there is a magical world available to each one of us that can see with our eyes closed if we could be a little more in touch with that world. Please give your hands a big high-5 for feeling the world all around you.

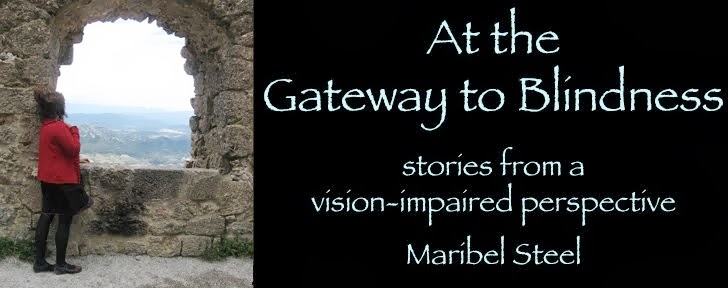

As I stand at the gateway facing the ever-diminishing sense of sight, my view of the world would be dim indeed, if my hands were bound together, and never allowed to reach out and touch what my eyes fail to see.

As if eyes reside on the pads of my fingertips, often roaming hands glide and pat, fingers feel and fiddle with everything my hands come into contact with, in an attempt to perceive the world. Sometimes, my grown-up children would prefer I keep hands laced together on those occasions when they witness my close shaves with precariously balanced fruit and fragile homeware perched on store counters.

‘Mum. Stop touching everything!’ comes their plea.

I interpret this as, you can come shopping, but don’t touch the merchandise. Expected to stand empty-handed in a store while others look around is like being thirsty in a cafe where everyone is placing their drink orders and excluding yours. So naturally, I ignore their misguided request for tactile decorum and keep feeling items on shelves, clothes in racks, food in plastic wrapping – to satisfy my curious fingers and inquiring mind.

Touching treasures

Family and friends who know me well will often place an item of interest into my open hand whenever they see something they know I would be allowed to touch and would enjoy ‘seeing’ too (possibly in an attempt to forestall fidgety fingers poised to lunge at items like a blind bull in a china shop).

Touch brings a deep sense of inclusion, where I can not only be brought into the picture of what others are seeing but I can also offer my own comments as I trace over the contour, feel the texture, delight in the shape of the item we are now both looking at.

Without wanting to sound like a touchaholic here, I have good reasons for my keen pursuit for tactile therapy, especially in retail stores and garden centres. To shop is an open invitation to touch: to touch is to see. I don’t have to buy anything I handle but where else is there such an open invitation for hands to browse? Not at a museum. Not at an art gallery. So naturally, my hands move around the goods on display on a market table, department store or garden nursery in a frenzied urge to oblige my all-seeing hands. I might add in my hands’ defence (your Honour) that seeing through the skilful movement of receptive fingers, they have rarely broken or damaged anything.

A Touch too keen

There have been a few times when my zealous partner has tried a little too hard to bring objects into my viewing hands. We were at a French museum when he gently guided my open palm to glide over an exhibit of a rare stuffed bird – until the curator came screaming towards us like a screeching banshee with its tail on fire! Harry shrugged his shoulders and held up my white cane with a baffled smile, nudging me away from the feathered bird, muttering an apology in French for my unrestrained actions.

There have been a few times when my zealous partner has tried a little too hard to bring objects into my viewing hands. We were at a French museum when he gently guided my open palm to glide over an exhibit of a rare stuffed bird – until the curator came screaming towards us like a screeching banshee with its tail on fire! Harry shrugged his shoulders and held up my white cane with a baffled smile, nudging me away from the feathered bird, muttering an apology in French for my unrestrained actions.On another occasion, while we were enjoying a romantic stroll through the scent-filled botanical gardens of Melbourne, Harry got the inspired idea to take me for a tactile tour around the cactus garden because rare flowers were in full bloom and large enough for me to see. Hesitantly, my fingers unfurled from the white cane to gently grasp the plant in his hand.

With much care and a deep intake of breath, I managed to avoid being spiked by the impressive serrated leaves of several cacti until Harry gathered up a fallen specimen from the mulched ground near our feet. He was so taken with the excitement of sharing nature’s little treasure, and to include me in seeing what he could see that, without thinking, he handed me the small fruit of the prickly pear, realising in the split second it took me to throw it back at him, that maybe, pulling out fine needle-like hairs from both our palms could have been better handled – if we had brought thick industrial gloves.

Blind parent – sighted child

When my son was very young, we shared a tactile communication: through puzzle play,clay moulding, Lego building, baking cookies. Michael learned to bypass my lack of sight by tracing shapes onto my open palm, knowing that when he did this, mummy could ‘see’ the object by drawing it. His little fingers tickled my palm and I held back tears of love for his thoughtfulness.

When my son was very young, we shared a tactile communication: through puzzle play,clay moulding, Lego building, baking cookies. Michael learned to bypass my lack of sight by tracing shapes onto my open palm, knowing that when he did this, mummy could ‘see’ the object by drawing it. His little fingers tickled my palm and I held back tears of love for his thoughtfulness.At kindergarten, we sat together on tiny wooden chairs by tiny wooden tables, feeling our way around puzzles. One particular day, the teacher was showing the little people how to bend paper to make a paper plane. Michael asked me for sighted guidance but I had no idea how to advise him. We persevered together, awkwardly turning the paper this way and that. If only I could see enough to help my son complete this simple task.

‘Now, just fold along this line, then turn the paper over this way and then…' the teacher held up her paper plane. The children gasped in awe.

‘Which way, Mummy?' Michael asked again. ‘Is this right?'

I replied, biting my bottom lip, 'What do you think, darling? Does it look like your teacher’s plane?'

He persisted with the folding of paper unaware of my silent tears. The teacher came over to our table, and rested a kind hand on my shoulder. My heart tripped with gratitude as she said to Michael,

He persisted with the folding of paper unaware of my silent tears. The teacher came over to our table, and rested a kind hand on my shoulder. My heart tripped with gratitude as she said to Michael,‘Clever boy. That’s nearly right.’

Back in the comfort of our home, and away from scrutinizing eyes, we continued our tactile communication. We collected cards of all sorts and cut out magazine pictures, chatting about the images, pasting them into our own large scrapbooks, remembering the scenes on each page. We sang funny songs and silly rhymes to spark his imagination and, at night, we made up our own stories.

But one night, as I struggled to read his favourite ‘Mr Men’ book at bedtime, I put down the magnifying glass and sighed deeply, ‘Oh dear, this is very slow, isn’t it, darling?’

Michael jumped up from under the doona, threw his warm arms around my neck, and said, eyes alight, ‘Mummy, don’t ever give up. Please tell me one of your stories.’

MEET ME WITH WORDS

A poem by Sarah MartinSometimes I feel the ocean

Like seaweed fingers on my back

Sometimes I feel the sand

Brush away the past held in my eyes

Sometimes I feel the breeze

Encouraging my life to exhale

Sometimes I feel the sun

Melt the darkness set in my heart

Sometimes I feel the rip

Pull me back once again

Sarah Martin is a Melbourne based poet who shares her experience of Retinitus Pigmentosa (RP) through creating poetry to melt away any darkness that tries to set in her heart. To read more of her inspired thoughts, you can visit her blog:

http://sarahjmartin.blogspot.com.au

Next post: The four main tools that live in my ‘blind tradie’ toolbox

© 2013 Maribel Steel